I suppose now is as good a time as any to introduce you to the world of Organic Theology and the movement towards reintroducing it into the church that I had found myself, somewhat unwillingly and unwittingly involved in. Organic Theology is mostly considered a peculiar branch of the movement known as Natural Theology. But whereas as Natural Theology took a philosophical view of evidence of God through nature, the people who founded the Organic Theology movement had a rather different agenda. From what I gather from the writings of the founders they found Natural Theology to be a little too broad and unhelpful for it’s needs. The founders – Epaphus Sykes, very much the ringleader of the group, and the like minded souls Gideon Pinkus, Augustus Cobb and Isaiah Walklate – were a group of who saw a distinct link between nature and their Christian faith but wanted to disassociate themselves from the philosophical trappings and theological baggage so many years of Natural Theology had brought with it.

Walklate and Cobb were the naturalists of the group, the first an academic of sorts and the other a gentleman farmer, both based in Hampshire in the early nineteenth century. Pinkus and Sykes were the clergymen both with a shared and deep fascination with the rural world. A fascination that especially intensified after a visit to the New Forest on a walking holiday. Full of the beauties of the place and it’s untamed glories they returned to see their friends the academic and the gentlemen farmer and promptly entranced them with their stories. So it came as not particularly a surprise that after much thought, they decided to form their little group to break away from the modern world and centuries of theological and philosophical thought and just focus on the notion of God purely as seen through nature.

They were not the first to be moved by the New Forest either. For generations the place has cast a spell. Famously there were stories of phantom stags seen in the forest just after the death of the much hated William Rufus in the late eleventh century. Certainly there always seems to have been some kind of mystical hold the strange, dense and isolated part of the country has had on the popular imagination. Something about it’s Eden like, mysterious, dense forests seemed to overwhelm many people – after all you saw what a self involved fool I became upon arrival – and they saw it as a way out of the horrors of the modern world. The nineteenth century was particularly full of them. The Organic Theologians in one corner. Pockets of Shaker groups, most famously the followers of Mary Ann Girling called the Girlingites, in another. In fact generally pacifists, utopians, cranks – all of them sought solace, or something nameless, in the depths New Forest. Even, word has it, witchcraft and Satanism flourished here and there in the isolated villages. They all looked deep for the answers to their many, many questions. I’m not sure any of them ever found the answers but something kept bringing them back.

But to me all of it speaks of a need to escape from the bits of the modern world they didn’t like. Some cynics would say, and I would count myself among that number, Organic Theology was almost entirely Natural Theology with all the actual meat and intellectual rigour gutted from it. Fundamentally it was purely the warmest, cosiest, woolliest thinking form of Natural Theology they could come up with. They were the religious equivalent of the sentimental, twee nonsense that you see so often on greetings cards. If the Lord is your shepherd, then we as His lambs are purely of the warm, fluffy and frolicking nature. There’s no attempt to deal with the darker part of human nature or even of nature itself. They just closed their mind from that part. And tried to escape from the bits of the world they didn’t like.

At theological college we had it described to us by our teachers, those who even bothered to mention it as it had been going through a particularly fallow few decades at the time, as possibly the least intellectually rigorous movement of them all. It was roundly considered that it purely existed for the type of Christian who didn’t like to be challenged in any obvious way at all. To be honest it was little more than a footnote for most of us during our studies, as for many clergy it was just an object of ridicule and folly and for others a warning of the extremes woolly thinking could take you to. It had never really captured much of the public imagination, at least certainly not as a theological movement – mainly because it wasn’t really a movement as such. It was almost the opposite of a movement because of that lack of a central idea behind it. If anything even approximating an idea ever threatened to loom over it the founders seemed to immediately discourage it. Rumour has it even Isaiah Walklate was ostracised from his own group for questioning this eventually.

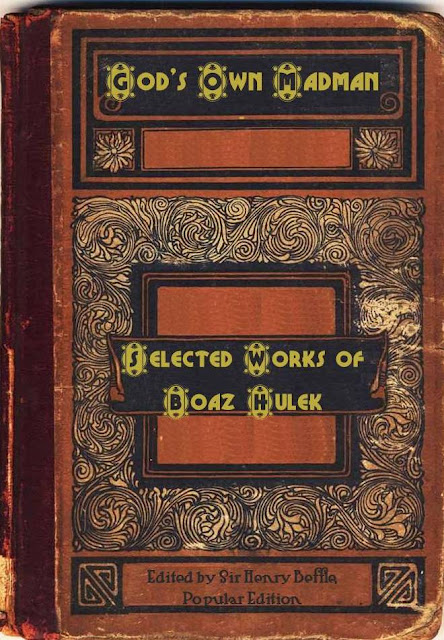

But the funny thing was that without really realising it, Organic Theology did take hold. Almost every home in the mid to late nineteenth century would have something by Cobb, Walklate, Sykes, Pinkus or one of their myriad followers – most famously the painter Oswald Melville, the poets Amos Bandicoot and Miriam Hentigrew, the novelist Jonathan Seaborn etc etc – all of whom bashed out terrifyingly vapid and sentimental tomes about the natural world which at some point or other may have invoked Christianity on some level but never actually threatened to challenge the reader. So what was intended to be a very simple theological movement just got seen as lovely, sentimental books ideal for grandparents to give to their children to read at bed time. I know that mine did, digging into a copy of Bandicoot’s The Riches of the Vine and plucking some dire little verse on the joys of nature when I stayed over at their house. It used to sit next to a copy of Martin Tupper’s Proverbial Philosophy on their shelf and I used to dread them ever reading me anything from either of them before bedtime. Even as a child I was a stubborn little so and so.

And so Organic Theology wouldn’t quite die. It was remarkably durable. Every so often it threatened the odd death rattle but then suddenly there would be some kind of revival of sorts, either directly through the founders or indirectly through the artists and writers they inspired. Certainly after almost every period of trial and tribulation in this country, particularly times of warfare, there was a sudden desire towards the simple and the uncomplicated as solace from the horrors of reality. And none came more simple, uncomplicated and fundamentally shallow as Organic Theology. It was uncomplicated and unchallenging in a world full of complication and challenges. I could understand that need to a degree because everyone wants solace in a world that makes no sense to them.

But understanding it doesn’t mean I want to attend a week long conference of the first attempt to revive the movement since the Great War.

Bishop Baddeley, my bishop, decided that I was far too cynical and prone to muddled thinking in my theology (meaning that I challenged things and demanded answers of all things) and as such I was called upon to attend this damned conference. And my heart frankly dreaded it. he had been part of a group of clergymen who had been idly tinkering with the central tenets of the movement – which was news to those of us who felt that the whole part of the movement was that it had no central tenets whatsoever – for the last ten years. And he felt it was just what I needed at this time of my life.

And that’s how I was pretty much sent to the New Forest that particular week in November 1930.

But even as the minibus, put on by the owners of Peverill House for their visitors, shuddered down the small, tree lined avenue approaching the house I realised quite how ridiculous Organic Theology really was. All the landscape and countryside I could see out of my windows was one that spoke of mystery and age and complications, just in the same way I felt my religion did. All this nonsense of reducing the timeless beauty of nature it to a bunch of foxgloves and hollyhocks and some mewling ponies was frankly insulting and irritating and frankly asinine.

But my bishop wouldn’t see it like that. And I rather liked my parish. And I liked having a job even more.

So, as the phrase goes, I sucked it up. And thus, here I was."